'Περί συγγραφής' - ολίγον από θεωρία

Δεν

χρειάζεται να ψάξει κανείς πολύ για να ανακαλύψει ότι υπάρχουν πάρα πολλά

βιβλία που έχουν γραφτεί γεμάτα με συμβουλές, υποδείξεις, παρατηρήσεις για το

πώς μπορεί κανείς να γράψει. Έχουν πέσει κάποια από αυτά στα χέρια μου με το

καλύτερο και πιο ενδιαφέρον ίσως αυτό του Stephen King, το ‘On writing’. Πιστεύω ότι τα περισσότερα

σηκώνουν πολύ ‘φιλτράρισμα’ και τα αποφεύγω πια. Έχει ενδιαφέρον όταν έχει κανείς γράψει έστω

και λίγο να αναλύει σύμφωνα μ’ αυτά που υποδεικνύουν γνωστοί και άγνωστοι ανά

τον κόσμο συγγραφείς τα κείμενα του. Απ’

την άλλη υπάρχει μια τάση να δημιουργούνται συγγραφικά μοντέλα, πρότυπα τα

οποία επικρατούν κι οποίος διαφοροποιείται να εκλαμβάνεται από την πλειοψηφία του

χώρου – εκδότες, επιμελητές, συγγραφείς - σαν εξωγήινος ή έστω εν δυνάμει μη

εμπορικός (!). Διαβάζοντας κλασική, μοντέρνα, σύγχρονη λογοτεχνία στην γλώσσα μας

αλλά και σε άλλες θεωρώ ότι βοηθάει στο να αποκτήσει κανείς μια σφαιρική άποψη

για το γράψιμο και ένα κριτικό πνεύμα που θα τον βοηθήσει στο προσωπικό του

στυλ χωρίς αυτό να σημαίνει βέβαια ότι δεν θα συναντήσει διάφορα εμπόδια στην

δύσκολη πορεία μέχρι την έκδοση. Μέσα

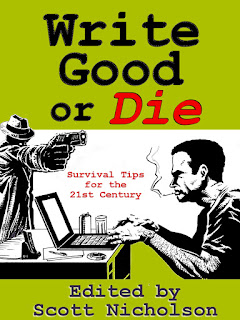

λοιπόν από αυτά που έχω διαβάσει παραθέτω πιο κάτω ένα άρθρο ενός άγνωστου σε

μένα συγγραφέα που μου είχε κάνει εντύπωση. Το είχα διαβάσει σε ένα ebook με

τίτλο ‘Write

good or die’ (!!). Κι αυτό όχι γιατί το θεωρώ πανάκεια αλλά διότι

πιστεύω ότι όντως εφαρμόζεται στα περισσότερα μυθιστορήματα και αποτελεί μια

καλή συμβουλή για κάποιον ο οποίος είτε κάνει τα πρώτα του βήματα είτε ‘ψάχνεται’

όπως συμβαίνει συνήθως με τον γράφοντα.

Ελπίζω

να με συγχωρέσετε που δεν έκατσα να το μεταφράσω, αλλά δεν είχα χρόνο … (η

αλήθεια είναι ότι βαριόμουν επίσης!!!)

The Three-Act Structure in Storytelling By Jonathan

Maberry

All stories are told in three acts, whether it’s a

joke, a campfire tale, a novel, or Shakespeare. The ancient Greeks figured that

out while they were laying the foundations of all storytelling, on or off the

stage. Sure, there may be many act breaks written into a script, or none at all

mentioned in a novel, but the three acts are there. They have to be. It’s

fundamental to storytelling. Here is the “just the facts” version of this. The

first act introduces the protagonist, some of the major themes of the story,

some of the principle characters, possibly the antagonist, and some idea of the

crisis around which the story pivots. The first act ends at a turning point

moment where the protagonist has to face the decision to go deeper into the

story or turn around and return to zero.

Often this choice is beyond the protagonist’s control.

In the second act the main plot is developed through action, and subplots are

presented in order to provide insight into the meaning of the story, the nature

of the characters, and the nature of the crisis. Also, supporting characters

are introduced, and we learn about the protagonist and antagonist through their

interaction with these characters. The second act ends when the protagonist

recognizes the path that will take him from an ongoing crisis to (what he

believes is) a resolution. In the third act, the protagonist races toward a

conclusion that will end or otherwise resolve the current crisis and provide a

degree of closure. Most or all of the plotlines are resolved, and the

protagonist has undergone a process of change as a result of his experiences.

Now, here’s the Three-Act Structure applied to the movie version of The Wizard

of Oz.

ACT ONE

In Act One we meet Dorothy, who is an obnoxious and

self-involved child who seems unable to recognize the existence of beneficial

relationships (with her aunt and nncle, the farm workers, etc.) and doesn’t

value these connections. She is so self-absorbed that she fails to accept that

anyone else’s needs/ wants matter, as demonstrated by the fact that she is

fully aware that her dog damages a neighbor’s garden and doesn’t care.

Actually, she

may be mildly sociopathic because she cannot grasp that “her” dog has done

anything wrong and ignores the fact that the dog’s lack of training is her own

fault. Dorothy ‘s whole focus is on what she feels she does not have and what

she deserves if only she can get to a better place (in her view, on the other

side of the rainbow). So, she’s shallow, vain, sociopathic, and unlikable. A

perfect character to have at the start of a novel, since character growth is a

primary element of all good stories. The crisis comes initially from pending

consequences from her dog’s vandalism.

Then a big storm comes along and whisks Dorothy away

to another place where (a) she has killed her antagonist through the proxy of a

witch who chanced to be standing where Dorothy’s house was landing; (b)

everyone she meets is substantially shorter, and therefore apparently inferior

to her –and her distorted self image; (c) a maternal figure appears and tells

her she’s special and that she has to go on a journey in order to solve her

dilemma; and (d) she gets cool shoes.Dorothy steps out of Act I and into Act II

when she places her ruby slippers the yellow brick road.

ACT TWO

In Act II, Dorothy begins a process of growth that

will expand her consciousness, increase her personal store of experiences, help

her develop meaningful relationships, and get her the hell home. When she meets

the Scarecrow and learns that it can talk and is in need of help, Dorothy has

her first opportunity for real character growth. Instead of bugging out of

there (a choice she may well have taken back home in Kansas), she helps the

Scarecrow down and even offers to share her adventure with him. If the wizard

she’s been told to find can help Dorothy get home, maybe he could offer some

assistance to someone in need of a brain. Off they go to see the Wizard.

Dorothy has performed her first selfless act. She may not be beyond hope after

all. When the Scarecrow and Dorothy meet the Tin Man, there is another

opportunity to perform a selfless act of charity. She does this; but this

encounter also requires her to do some problem solving. The oil can shows

intelligence and practicality. Good for her. Now she has helped two others in

need, and at the same time she has increased her circle of valuable friends.

This adds to her bank of useful experiences and also

increases the odds of success. The three of them (and her little dog, too),

then encounter a frightening attack by a lion. In a real-world setting this

would end badly, except for the hungry lion. But in this metaphorical tale, the

lion is also a complex and damaged individual whose violent nature is a cry for

help. However Dorothy doesn’t know this at first. The Lion attack and Dorothy

stands between this threat and her friends –and even attacks the Lion (albeit

with a slap across the chops). This is a brave act that is selfless to the

point of sacrifice.

Dorothy is actually pretty cool now. Hero Dorothy.

Luckily the Lion is a coward, and we see Dorothy shift from attack to sympathy.

Again this shows character growth in the form of a refined insight into the

needs of another. Dorothy, now in the role of matriarchal clan leader, accepts

the Lion into her pack, and the four of them go off to see the wizard. All

through this the Wicked Witch of the West, sister of the house-crushed Witch of

the East, is after Dorothy and her ruby slippers. We never truly learn why (a

storytelling shortfall explored later in novels and Broadway plays), but as a

threat the Wicked Witch is constant and pervasive. She is enough of a threat

that her presence, or the fear of how her anger might be manifested, influences

the actions of every character in the story. Dorothy and company overcome all

obstacles and finally make it to Oz, home of the Wizard. There they present

their case and the Wizard agrees to help but throws them a plot twist.

He’ll help only if Dorothy undertakes a quest to steal

the broom of the Wicked Witch. Dorothy, however reluctant, agrees. This is

huge. The Dorothy we met in Kansas not only could not have accepted this

mission; she would not have. However the Dorothy who stands before the great

and mighty Oz is a far more evolved person who has benefited from adventures

and experiences that have revealed her own strengths, demonstrated the power of

friendship and collaborative effort, and basically served as a boot camp for

Hero Dorothy. As Dorothy and company step out of the Emerald City to begin this

quest, they step out of Act Two and into…

ACT THREE

In Act III, Dorothy and her team covertly assault the

stronghold of the Wicked Witch. They formulate a master plan and carry it

through, albeit with some unforeseen complications (we love complications,

catastrophes, challenges, calamities, and other C-words that make it more of an

effort for the good guys to win). They sneak into the castle, and there is the

long-anticipated showdown between Hero Dorothy and the Wicked Witch. We get a

twist when the Witch catches fire and Dorothy, in a demonstration of compassion

even to her enemies, tries to douse the flames with water. And this leads to

one of those “Ooops!” moments that enrich a story: the water is fatal to the

witch. (Leading one to wonder why she has a bucket of it to hand.

Depression? Thoughts of suicide? We’ll never know.)

With the Wicked Witch dead, Dorothy discovers that the Witch was also a tyrant

and now the people of her land rejoice for freedom with a rousing chorus of

‘Ding Dong the Wicked Witch’ (which they sing in immediate harmony, suggesting

that this is a long anticipated eventuality). Dorothy and her posse bring the

broom back to the Emerald City and BIG TWIST: the wizard is a fraud. All smoke

and mirrors. No real powers. Damn. Did not see that coming.

However the Wizard has a heart of gold in his

deceitful chest, and he hands out some baubles that symbolize the things

Dorothy’s friends need: recognition of innate intelligence, acknowledgment of

dedication, and a reward for valor. Nothing for Dorothy. The Wizard then

attempts to take Dorothy home via hot air balloon, but that ends badly and the

Wizard floats off to who knows where, alone. And, one wonders if that escape

had been planned all along. Devious bastard. Finally the Good Witch shows up

and in another BIG TWIST, tells Dorothy that she had the power to go home all

along. The

ruby slippers are apparently good for interdimensional travel.

We see another element of Dorothy’s growth: restraint.

She does NOT leap on the Good Witch and kick the crap out of her for not

telling her this way the hell back in Oz. The Good Witch apparently recognized

the need for a vision quest and played the ruby slipper card close to the vest.

So, Dorothy bids farewell to her friends in Oz, clicks her ruby slippers and

wakes up in Kansas where she is surrounded by her Aunt and Uncle and the farm

workers, all of whom are ciphers for the characters she met in Oz. Or,

perhaps, vice versa. Dorothy now recognizes the value

of what she has and is properly grateful for it. Which allows us the change to

step out of the story, since we now know that it’s safe for Dorothy to continue

on her journey. We trust that she will do well because we’ve seen her growth,

and we know the cost.

If you look at the first Star Wars flicks, you can see

an almost identical process in Luke’s journey from annoying dust farmer to

someone who can blow up a Death Star. So, that’s the short and long of the

Three Act Structure. You may not be able to watch Wizard of Oz the same way

again; and if you’re a true writer, you’ll be forever plagued with trying to

identify the act breaks in every book, TV show or movie you ever watch.

Don’t blame me… blame the Greeks.

Jonathan Maberry— http:// www.jonathanmaberry.com

Σχόλια

Δημοσίευση σχολίου